Urethral Distraction Injuries

Urethral distraction injuries occur in up to 10 percent of pelvic fractures and are mainly due to high-speed motor vehicle accidents and occupational injuries.

- Urethral strictures develop in nearly all patients after a complete urethral disruption. Initial management by primary realignment appears to decrease overall stricture incidence.

- Three to six months after initial injury, the prostate and bladder descend as the pelvic hematoma (clotted blood) is reabsorbed and organized.

- The eventual stricture length is commonly only 1 to 2 cm. Such relatively short strictures can be bridged easily by a one-stage urethroplasty.

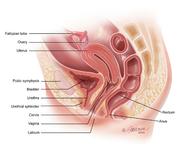

- The stricture involves, to varying degrees, spongiofibrosis of the distal bulb and membranous urethra. The other potential segments of “stricture” are not true strictures of the urethra, but rather scar tissue in the intervening space between the dislocated prostate and the pelvic diaphragm.

- Less then 10 percent of urethral strictures are complex, that is, with long urethral defects (greater than 6 cm) or associated with anterior urethral strictures, rectal or bladder neck injury, fistulas (abnormal passages), or chronic cavities in tissues surrounding the urethra.

Stricture Evaluation

- Although newer imaging methods, including ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have been employed, dynamic fluoroscopic imaging with simultaneous voiding cystourethrography and retrograde urethrogram remains the gold standard. When fluoroscopic images are confusing, MRI is helpful in surgical planning.

- Before being considered for urethral reconstruction, the patient also must have:

- No evidence of pelvic abscess or infection

- A competent bladder neck. Since the external/membranous urethra is damaged, a competent bladder neck is essential to assure continence after reconstruction. A static cystogram followed by urinating can assess bladder neck function.

- No urethral instrumentation in the last three months (the scar must be stable).